Reflecting on Azamgarh: Part One

As I have said, some journeys exist only in memory.

One memorable journey. Four posts.

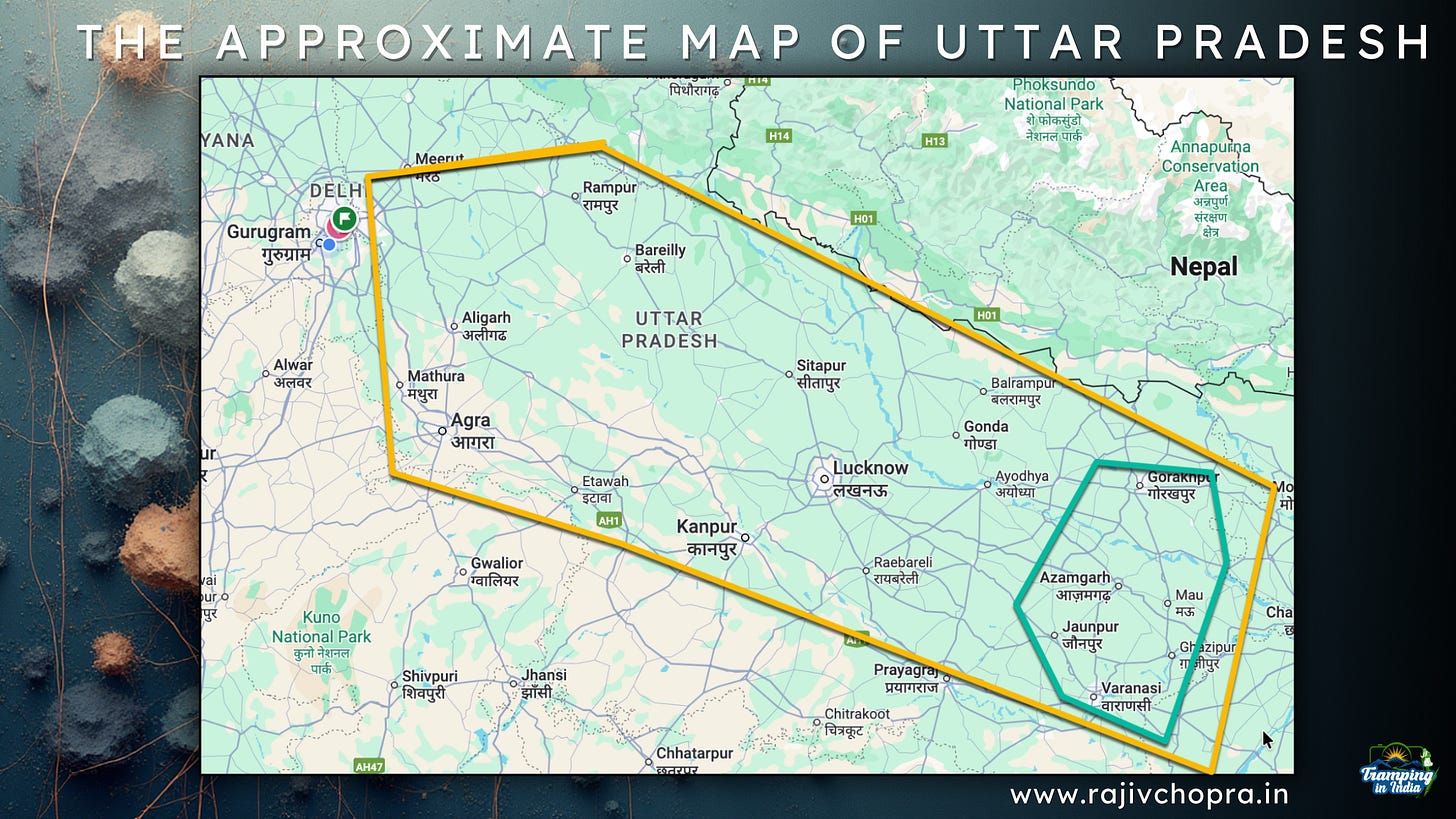

I had planned to write a blog post about my memories of several journeys or incidents that are now just amusing recollections. Still, the sudden memory of a long-dead tawaif jerked me away from that direction, and put me on the path to writing a four-part essay about a young, insignificant – and dusty – town called Azamgarh in the eastern part of Uttar Pradesh in India.

Maybe I will use this year-end essay to write about a journey to Azamgarh, focusing on the trip to that tiny town. As I said, I intended to write about that journey as part of an essay of recollections, culminating in a final blog post for the year.

Buxar and history.

In an earlier post, I wrote about my thirty-minute walk in Buxar, trying to get a sense of the lost history of the Battle of Buxar, but all I found was a crowded, dirty, crude town where people rushed about like crazy lunatics. Since then, I have tempered my initial judgmentalism and have become more egalitarian, realizing that many people really struggle to make ends meet.

Yet I must also mention that we – like many people across the world – are ignorant of our history, allowing outsiders to write it for us or permitting politicians to create myths that masquerade as history.

Now that I have permitted myself that brief outburst, it’s time to get on with the matter at hand and speak about that amusing trip to Azamgarh.

John Muir and Ballia.

Once again, I remind everyone that I arrived at Buxar by train from Delhi, and caught a crowded motorcycle rickshaw to another tiny town, Ballia, at the eastern border of Uttar Pradesh. Ballia is on the banks of the Ganga, and even though it was May, with its scorching heat and burning sun, I did not miss the absence of air-conditioning in my hotel room. The breeze, cooled by the river’s waters, the moonlight streaming through my hotel window, and the sound of the flowing water worked better than any sleeping medicine can ever work, and, after a day working in the market and chatting with my distributor, I drifted off into peaceful slumber.

The mountaineer, John Muir, once said, “In every walk with nature one receives more than one seeks.” I did not walk with nature that night, and even though I was in my hotel room, the proximity of the river gave me a good night’s sleep a few decades back, for which I am grateful to this day.

If I can remember the gift of sleep the river gave me all those years back, and if you can appreciate what I am writing, then you will understand the meaning of John Muir’s statement.

The ruthless world of consumer sales in India.

I spent a day in Ballia, then took a bus to another tiny town called Ghazipur. After finishing my work in Ghazipur, I took another bus to Azamgarh and then returned to Benares. Lots of bus travel, as you can see! While traveling by state transport buses was not always fun, they had advantages over private bus operators, as you will learn.

One, they adhere to fixed schedules, which is an advantage. Second, since no rapacious businesspeople own them, the state does not pressure the conductor to stuff the bus to the gills. Third, they stop for chai midway. Apart from indulging in chai and local biscuits, I’d walk around to check on the availability of our products.

If our products were available and well displayed, the sales representative could live to see the day end well. If not, I’d unleash hell on the poor, unsuspecting fellow, and he’d often spend the evening frozen, his glass of rum in his hand, wondering if he should take a sip or not. The consumer sales business in India demands ruthless behavior, and – to use the cliché – we don’t take prisoners. If your product was missing from the shelf, it was always bloody difficult to convince the shopkeeper to restock it, and often involved lots of negotiation because the greedy little fellow always demanded special discounts to restock our – anyone’s – product.

The consumer sales business is cutthroat, physically and mentally exhausting, and if sales managers like me displayed any tolerance, we’d lose business. I’ve fired and transferred people, sometimes with just one day’s notice, and this behavior did not make me feel proud or more manly. We could not afford laxity. Dealing with salespeople who live and work far from the head office, we also had to contend with the reality that the salespeople often had cozier relationships with the distributor than with the company. The distributor gave the salesman a place to sit, chai to sip, and, if the sales rep’s family also lived in the town, the distributor often ensured their well-being when the sales rep went on tour. We recognized the sometimes familial nature of the relationship and did not disturb it, except when it impinged on the company’s business.

My amusing journey to Azamgarh.

And now, I shall describe that fateful, now amusing, story of my journey to Azamgarh, a journey that imprinted the town on my memory forever, or, at least, as long as I live.

By this time, my boss had become a bit less stingy and allowed us managers to take taxis between towns. I want to say that he became generous to please his now-dead soul, but that would be a lie. My boss taught me a lot about the consumer sales business and played a seminal role in transforming me from a cute boss to a hard-nosed one, but he was a stingy man.

Phase One. The Bus.

I flew from Delhi to Benares (we used to take the train earlier), and inquired about the cost of a taxi to Azamgarh. When I discovered that the taxi driver wanted to charge me more for the cab than I paid for the airfare, I took an auto-rickshaw to the bus stand, to catch (obviously) a bus to Azamgarh. I had just missed the state transport bus and did not wish to wait three hours for the next bus. So, I bought three tickets on a private bus. Three tickets guaranteed me the space of one-and-a-half seats, and helped prevent the cheeks of my bum from being squeezed into an unnatural shape.

The bus stopped halfway at a village called Lalganj, and all the passengers except for me got out of the bus. They were on to something, and I was in the dark. After ten minutes, the bus conductor boarded and ordered me into a crowded taxi that would take us the rest of the way to Azamgarh. His answer to my question was rough and impatient, but I learned that the bus had a licence to drive only to Lalganj, and that they had arranged for a jeep to take us to our destination.

Phase Two. The Jeep and the Goat.

My three tickets were now useless, and other villagers had taken the front seat in the jeep. I got into the back, and I promise that there were at least twenty people at the back of the jeep with me, even though it seemed as though there were one hundred people. I squeezed in and spread my legs, my suitcase on one knee, and my plastic briefcase on the other.

Before claustrophobia could seep into my soul, another villager with his goat got into the taxi. The man shoved the goat between my legs and sat on the rear edge of the cab, one bum cheek inside, and the other bum cheek flapping in the hot breeze.

Under normal circumstances, I would have wished a wedgie on him, but his goat wedged its mouth close to my testicular region, and I had no intention of moving, lest the animal decide to nibble. I had every intention of preserving my manhood and wished to secure the safety of my future descendants, so I held my breath until we reached Azamgarh.

Phase Three. The hotel has no towels.

On arriving at my destination, I went to the hotel and rented the most expensive room in the town. The room cost me a glorious sum, the equivalent of three American dollars a night. Inside was a steel bucket, but the room had no attached toilet or bath. The hotel expected me to carry my bucket to the basement for my bath and ablutions.

Not only was the room sans an attached toilet, but it was also sans a towel. When I marched to the reception to demand a towel, the receptionist refused! We argued back and forth, and it turned out the man had decided I was a thief who would steal the towel. When I offered him a deposit of three American dollars for the towel, which he would return on my departure, he looked at me as though I were crazy, but reluctantly handed me a towel as thin as a paper tissue.

The room’s saving grace was that it stood on the banks of a stream and, like in Ballia, the water cooled the breeze at night, allowing me the deep sleep of the innocent, or the damned.

And so it was that Azamgarh, despite its otherwise insignificance in today’s world, imprinted itself on my brain. But as I learned recently, the town was not always insignificant. You, however, must wait a week until my next essay on Azamgarh.

Until then, I wish you all a very Happy New Year and hope you will behave yourselves as you celebrate the turn of the year.

I had to use Midjourney AI to generate an image of a crowded taxi-jeep. Why? I could not find a single free-access image online.

Yes, hope any 2026 nibbling goats keep their distance.

Happy New Year! Thanks for your tales of traveling the dusty roads to small villages with difficult travel and spartan hotel accommodations. It's good to know that being able to hear a river helps one sleep well. Also that at some hotels, you need to bring your own towel. Imagine the hubbub if that requirement was placed for a stay at a Western hotel because they were tired of people stealing the towels. Hope that there are always towels at every hotel you stay in 2026!